Repin’s “Ivan the Terrible:” Patterns in the theme of modernity

In early October 2013, a group of friends sent a letter to Russian Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky and State Tretyakov Gallery Director Irina Lebedeva—and, eventually, to President Vladimir Putin himself—asking to remove Ilya Repin’s painting, “Ivan Grozny and his Son, Ivan, on Nov. 16, 1581,” from the Tretyakov Gallery’s permanent exhibit, describing the work as “a nasty, scandalous and false painting both in its subject matter and its pictorial representation.” The text of the letter, which was posted on the website of the Saint Vassily the Great cultural and educational fund, continues to be hotly debated in the media and on the Web. What do we make of this seemingly laughable letter? Is it a joke, a test of sanity, or yet another warning sign?

After the event, the media’s first reaction was to get the comments of the direct recipients of the letter, Vladimir Medinsky and Irina Lebedeva. In his discussions with RIA Novosti, Medinsky said he considers the entire matter a joke.

“Historians may continue to argue, but the archives of the [Russian] Ministry of Internal Affairs do not contain a bloodied scepter covered in fingerprints,” said Medinsky. “We know for certain that Mozart wasn’t killed by Salieri, and [Tsar] Boris Godunov, judging by all evidence, had nothing to do with the murder of [his son] Tsarevich Dmitry.”

“However, that doesn’t mean we should change our approach to the genius compositions of Pushkin and Repin,” he added. “Because there’s history, and then there’s art.”

This was a serious statement coming from a minister who wrote his Ph.D. dissertation on “The Problem of Objectivity in the Process of Illuminating Russian History in the Second Half of the XV-XVII Centuries,” and authored a series of historical books titled Myths about Russia. Medinsky also initiated the effort to establish a council on research and methodology within the Ministry of Culture that would conduct expert analyses of screenplays for documentary and feature films about historical subjects. Medinsky had earlier been part of a committee established by then-President Dmitry Medvedev to counter attempts to falsify history “to the detriment of Russia’s interests.” As such, it is good news that Medinsky, a leading advocate of historical truth and a strong opponent of historical falsification and slanderous fabrication, recognizes the right of the “creative worker” to exercise his artistic inventiveness when working with historical narratives.

Tretyakov Gallery Director Irina Lebedeva likewise noted that Repin was first and foremost an artist, not a historian, and suggested that the entire effort around the letter to the minister was nothing more than a publicity stunt, an attempt by the group to draw attention to itself. Overall, most observes concluded that the letter was an act of absurdity, but one that nonetheless reflected a troubling situation in the sphere of Russian culture—in which publications of this nature have gone from being singular instances of delusion to becoming more or less the norm.

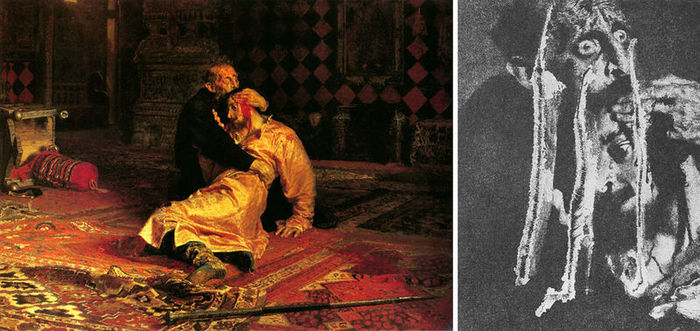

What I find significant is the fact that the situation with Repin’s painting reflects a broader symptom of the fever that has taken hold lately in the sphere of cultural politics. At one time, Russian painter and art critic Ivan Kramskoi noted that “historical scenes should only be painted if they provide a canvas, so to speak, for patterns on the theme of modernity, when a historical painting can express, one can say, the living, palpitating interests of our time.” What’s more, the above was written precisely in reference to Repin’s “Ivan the Terrible,” a painting which, to Kramskoi’s dismay, did not seem to fit into his theory. But first glances are misleading. If we dig a little deeper, we can quickly recall the prolific pronouncements of Repin scholars and of Repin himself that suggest the idea behind “Ivan the Terrible,” which the artist began to paint in the early 1880s, was tied to the assassination of Tsar Alexander II and the execution of members of the left-wing terrorist organization Narodnaya Volya [“The People’s Will”], who were behind the killing. In other words, the painting was tied to the most “living, palpitating interests” of the time.

In one of his characteristic statements on the subject, Repin said: “The contemporary craters, which had only recently inhaled the fumes of life, were now smoldering, still warm…It was scary to think about it—things would turn out badly… It was natural for people to seek a way out of the painful tragedy of history….The scene began inspiredly, moving forward in great strides… Man’s emotions were overwhelmed by the horrors of modernity…”

In another statement on “Ivan the Terrible,” Repin said: “Misfortunes, living death, murders and bloodshed constitute a magnetic force so powerful that only the highly cultured individual is able to resist it. At the time, every exhibition in Europe included large numbers of bloody scenes. Having likely been infected with this bloodiness, I returned home and immediately began to paint the bloody scene of ‘Ivan the Terrible and his Son.’ And this painting of blood was met with significant acclaim.”

Repin’s masterpiece indeed became a “canvas for patterns on the theme of modernity;” all the while, these same patterns were being stitched out by “highly cultured individuals” who opposed bloody scenes. In a sense, “Ivan the Terrible” became a gauge for making sense of the highly cultured class in particular, and the present-day social structure as a whole. For this reason, reactions to the events surrounding the painting were always revealing. This was true of the forbidding of Pavel Tretyakov, who acquired the painting, “to put it on display or otherwise permit the spread of the image among the public in any other form,” and the installment of the censorship that would increasingly plague the exhibitions of the Peredvizhniki collective in which Repin took part (the painting was exhibited at the group’s 13th exhibition).

Or take the event of 1913, when the painting was attacked with a knife by a mentally ill member of the Old Believers, Abram Balashov. Aside from causing a perfectly understandable public outcry, the incident ignited a debate within the art community. It began with an article by the poet and artist Maksimilian Voloshin, titled “On the Meaning of the Catastrophe that Afflicted Repin’s Painting,” published January 19, 1913 in the newspaper Russia’s Morning. In it, Voloshin justified Balashov’s act and ascribed it to “the very artistic essence of Repin’s painting.”

Afterward, Voloshin spoke about the painting at a lecture and debate organized by the Knave of Diamonds, an avant-garde artist collective, at Moscow’s Polytechnical Museum: “Its preservation is important in the same way as the preservation of an important historical document. But the painting itself is harmful and dangerous. If it displays talent, then it becomes even worse. It has no place in the National Picture Gallery, an institution that continues to shape the artistic sensibilities of our younger generations. Its true place is in some big European curiosity museum, like the Musée Grevin. There, it would become an ingenious specimen of its genre. There, it wouldn’t be able to fool anyone: those who go there already know what kind of experience is in store. But since the above scenario is impossible, the leadership of the Tretyakov Gallery has the responsibility to at least hang the painting in a separate gallery with a sign that reads, “Entry for adults only.”

Despite their differences in scope and argumentation, the incident with Voloshin somewhat resembles the group letter to Vladimir Medinsky and Irina Lebedeva. But Voloshin was treated much more harshly than his modern-day counterparts: his speech garnered such a hostile reception that newspapers and other publications slapped him with a full-on boycott and ceased to print his work.

Now, let’s take a look at the arguments against Repin’s painting that the latest group “indictment” puts forth. In other words, let’s imagine that on the basis of the recent letter, we can reconstruct modern-day ideas about aesthetics and cultural values that are forced upon society by the current government, the body to which the authors of the letter are appealing with arguments that, in their view, the government should absolutely take into consideration. So how does the picture look?

According to the letter, Repin’s painting constitutes an “act of slander against the Russian people, the Russian state, and Russia’s devout Tsars and Tsarinas.” The very first lines of the letter outline the various spiritual components that have been “slandered” in the painting: the people, the state, the notion of piety and the monarch. The words “slander,” “slanderous,” and other words of the same root appear in the text a total of 12 times. Recall that in July 2012, the Russian president signed a law on amending the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation to reinstate the article on “Slander,” which had been eliminated by the State Duma a year before. Apparently, the amount of slander in that year had begun to reach dangerous proportions, but the reason behind it is a different story.

“The version about ‘filicide’ appears only as a rumor,” the letter continues, “with the caveat ‘some say,’ in written sources dating back to as late as the 17th century that were created during or after the Time of Troubles and were based on the notes of obvious enemies of Russia, foreign emissaries…” Naturally, the obvious enemies of Russia (of its people, its state, its piety and its monarchs) were foreign emissaries. Here it would be fitting to mention the Russian law on foreign agents that went into effect at the end of last year, and that President Vladimir Putin recently said should be improved after admitting it wasn’t “completely smoothed over”—not to mention the recent documentary “Anatomy of a Protest 2” that ran on the state-run channel NTV, which argued, in part, that the protest movement in Russia had been financed from abroad.

“Russia and the Russian Tsar became the target of slanderous propagandistic pamphlets, while European citizens were spooked with stories about Russian soldiers. And the echoes of this slanderous propaganda war waged by Russia’s enemies are still visible to this day…” The reader doesn’t even need a reminder of the propaganda war portraying a false image of Russia that is supposedly being carried out among European citizens even today.

The letter goes on: “We, the Russian people, should be eternally grateful to our forbearers for creating such a powerful state <…> And no small amount of credit belongs to Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich the Terrible, who expanded the borders of our nation to include the kingdoms of Kazan and Astrakhan, and—most importantly—the kingdom of Siberia, whose riches of oil and gas the country lives on today.” Sure enough, it’s scary to imagine what our country—and its government in particular—would look like today if it weren’t for the great successes of Ivan the Terrible in conquering vast treasure troves of gas and oil.

Repin’s painting “produces a deep psychological and emotional effect on the viewer, <…> literally imprinting a slanderous message about Russia and its history upon the memories of thousands and thousands of visitors to the Tretyakov Gallery, a large number of whom are children who have not yet developed a critical approach to the world.” Children present yet another weighty argument: children who must always be shielded from various horrors, and whose protection has been the focus of so many recent laws and legislative initiatives.

“We ask that until the issue surrounding the painting is fully resolved, you remove it from the permanent exhibit of the Tretyakov Gallery and place it into storage, where it would stop offending the patriotic feelings of Russian people who love and cherish their ancestors and who express gratitude to them for creating a great and powerful nation—the Russian Orthodox Empire.” Here, as in multiple other parts of the letter, we find an appeal to patriotism and orthodox faith. But this particular, final paragraph has another important feature. The group writes about the “final resolution” to the issue surrounding the painting—yet it is writing to the minister about this “issue” for the very first time. This leads us to believe that the issue is already resolved, though not fully (it seems the group sees an ally in the Minister of Culture, who is certain to take on the task of resolving it). In other words, the painting should be moved into storage in advance¸ until the final resolution of the issue. But what happens after the issue is fully resolved: what should we do with it then?