Farewell, modernist aura!

In February 2012, the steering committee of Norway’s Bergen Assembly contemporary arts triennial announced the appointment of Moscow curators Ekaterina Degot and David Riff to serve as the organizers of the event. The leadership team of the inaugural Assembly includes a number of Russian participants: artists Dmitry Venkov, Dmitry Gutov, Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, Yury Leiderman, Andrei Silvertsov, Pavel Pepperstein, Aleksandr Rodchenko, Maksim Spivakov, Pyotr Subbotin-Permyak and Olga Chernysheva, along with the art groups Chto Delat?, Nest, and Urban Fauna Laboratory, and philosophers Keti Choukhrov and Boris Grois. The actual title of the exhibit was borrowed from the cult sci-fi novel by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky, “Monday Begins on Saturday”.

It’s a difficult question: How do we stage an exhibit of political art (and do so politically) after everything that has happened to us? Here’s a brief summary of the previous episodes. In October 2008, we witnessed the flare-up of the financial crisis. Its many side effects initially promised to be fatal to the art world, but in the end the art world managed to stay afloat, albeit with varying success across the globe. For artists and curators, who tend to think globally, the financial fallout became motivation to come up with an alternative to the excessive and glamorous lifestyle enjoyed by the international art community.

Leftist ideas once again began to attract widespread popularity. The 2009 Istanbul Biennial, organized by the group What, How & For Whom, centered on the fight against capitalism. The 2011 biennial, curated by the Costa-Rican born Jens Hoffmann, explored the imperceptible art of the empty gesture, the document and its artistic interpretations, and modesty as a mode of self-expression in the age of neoliberalism. Then, in 2012, the Polish artist Artur Zmijewski invited the Occupy movement and the group Voina to participate in the Berlin Biennial. For many people, these two social movements carried the hope of political and economic change. Willingly or unwillingly, Zmijewski staged the perfect experiment by giving Voina and Occupy the chance to operate in a zone of legitimacy and thereby to find out for themselves whether they’re shaky, ready-made movements or something truly worthy of respect.

Each of these exhibits stemmed from the idea that if art doesn’t change the world, then it should at least address the question of how to do so. The world has admittedly changed over the last several years. But the escalation of various conflicts in the political sphere has been nothing compared to the heightened aspirations of leftist art. We have recently begun to see exhibits of a different kind, such as dOCUMENTA(13) by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev and Encyclopedic Palace by Massimiliano Gioni, the centerpiece project of the 55th Venice Biennial. The emphasis on irrational art is considered by leftists to be reactionary anti-intellectualism. They want fresh ideas. And the Bergen Assembly is rife with them. If there is any justice in the world, then this new exhibit will propel Ekaterina Degot and David Riff to the highest league of curators in recognition of the originality and superior quality of their work. Let’s hope that in the future, they’ll be invited to work in a warmer climate—or at least one that can be reached by a direct flight from Moscow.

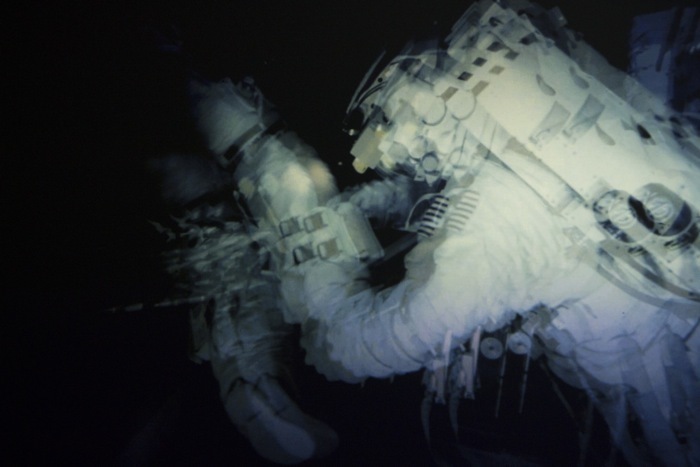

The curators of this exhibit do not concern themselves with discussions about the extent to which art influences politics. To them, the political role of the artist as the initiator of social change is not a valid topic at all. Instead, Degot and Riff evaluate leftist art through a futurological approach. That means, on the one hand, that the exhibit includes a large number of fantastical pieces in various mediums. Take the crisp, slightly art-house film “Like The Sun,” perhaps the best example of video art in this category, co-directed by the winner of the 2012 Kandinsky Prize, Dmitry Venkov, and Rodchenko Moscow School of Photography and Multimedia graduate Antonina Baever. It’s a hipster version of Besson’s “The Fifth Element,” with a surprise ending: three oddball young people create a second sun in the Moscow sky with the help of camel milk and ocean water. Science fiction plays a big role not only in the exhibit but in the accompanying catalogue, where nearly half of the articles—including a fresh piece by Russian conceptualist Pavel Pepperstein—explore the subject of utopia and anti-utopia.

On the other hand, there are works that don’t fall into the sci-fi genre but which retrospectively take on a new resonance, not making a direct statement but exuding a kind of potential, a single scenario out of many possibilities. These works are based on the classics of Russian literature, which allows them to relax and see themselves from the side. The very process of creating an exhibit for a global audience is full of inherent contradictions. The curator has to make sure the exhibit contains a certain system of checks and balances, lest it appear dogmatic. In Russia, it is possible (but hardly necessary) to build exhibits in the trenches (meaning, in inhospitable locations); Degot and Riff’s earlier project “Shockworkers of the Mobile Image” for the first Ural Industrial Biennial in Ekaterinburg is a perfect example. At the same time, even in some of the most comfortable parts of Europe, rigorous and didactical pieces are unable to find an audience. That’s why curators will nobly steer clear of such works in favor of creating an inclusive rather than an exclusive exhibit. They may even package their project with a move reminiscent of traditional social art. For example, one of the sponsors of the Bergen Assembly is the fictional Chinese governmental organization, Zi Qi Dong Hai. A statement by the organization’s representatives appears in the catalogue immediately following the welcoming remarks of the Assembly chair, and contains several hilarious passages about “so-called Western democracy” that could stand to benefit from the support of an experienced China. Degot declined to disclose who was behind this conceptual gag. If anyone knows, please leave us a comment.

At the core of Degot and Riff’s project is the famous novel by the Strugatsky brothers, “Monday Begins on Saturday.” The novel has been largely forgotten at home, and the Western reader has only limited knowledge of it; it was clearly read by the artists and participants of the exhibit, but not by the vast majority of the international art criticism scene. As a result, the Russian patron has a distinct advantage over other visitors to the Assembly. An even greater advantage is to be had by those who, like me, enjoyed the novel and re-read it from time to time. Of course, few of the book’s fans would call it a work of “neo-Leninism,” as it was described by the curators in the introduction to the catalogue. The novel can be interpreted this way only as a product of the “thaw” period, a time during which the “return to Leninist principles” was the main rallying cry. However, even those who espoused this slogan were aware of its double uses. For bureaucrats, it was a way to protect oneself from false accusations; for the intelligentsia, it meant greater freedom of speech and assembly. But that is beside the point: for Degot, it has always been characteristic to adopt a slightly more opinionated stance.

The exhibit spreads out over 11 venues across the city, from state museums to various non-commercial spaces. The name of each venue includes the word “institute.” Sometimes, the names coincide with the names of the departments from the novel’s Scientific Research Institute of Sorcery and Wizardry. Other times, they are invented by the curators themselves. An example of the latter is the Institute of Tropical Fascism by Colombian curator Inti Gerrero, which features an exhibit within an exhibit. In each room, the viewer runs into several repeating elements: an electric clock, a quote from the novel, and a potted ficus plant. These nuanced exhibits, like the novel itself, can only be understood by people from Russia; I recall having to explain to another visitor that this kind of clock and plant were the staples of the Soviet office interior.

The simple packaging of the exhibit serves as a highly accessible and even enticing prelude to the exhibit itself. The guiding principle behind the piece selections, however, is recognizable and fairly characteristic of a serious, left-leaning exhibit. For one, it includes many variations on the theme of architecture and public space. More than any other visual art, architecture—and especially postmodernist architecture— is closely connected to the socio-political environment of the day. As such, it has become a particular interest of leftist artists and has provided an endless source of topics for research and speculation. To illustrate this point, the first part of the exhibit, the Institute of the Disappearing Future, starts with a photographic series by Angolan artist Kiluanji Kia Henda titled “Icarus 13” (2008). The artist takes photographs of 1970s architecture in Angola and uses its modernist shapes to craft a touching narrative about the launch of the first African into space.

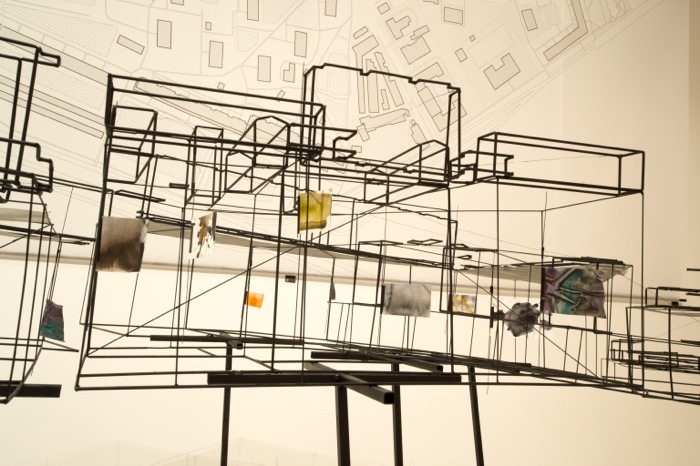

The adjacent space houses a sprawling installation titled “The Island (2013)” by the Ukrainian duo Group of Objects (Ivan Melnychuk and Oleksandr Burlaka). It’s a model of an enormous estate, created by a former modernist for the new lord of contemporary life, the anonymous oligarch. The model is accompanied by a plethora of visual materials and a letter in which the fictional architect explains his project to his client: “The only thing I regret is not having been endowed with the qualities that would allow me to fight next to You in defense of Your ideals. I offer You my experience and artistic sensibilities as a humble gift. I hope it will be enough to bring glory to Your good deeds and rid your enemies of even the slightest expectation that Fortune may fall on their side.” The entire complex is composed of more than 10 buildings and stands on a territory with a public park and a stadium. In his project description, the architect also includes plans to construct a contemporary art museum, noting that “this museum will showcase Your priceless collection and should serve as worthy compensation for the fact that the citizens of the city will no longer be able to use the island. I assure You that, having had a chance to see the masterpieces of world art, they will forget about the pitiful pleasures they once reaped from this bygone island.”

In visual terms, “The Island” is strongly reminiscent of installations by the conceptual artist Ilya Kabakov, but in substance it has more in common with the prominent conflicts of modernity, from the architectural advocacy efforts of the Moscow-based Archnadzor to the recent demonstrations on Istanbul’s Taksim Square. With this installation, Group of Objects also seems to be commenting on the fierce debate between the “old” and “new” representatives of Ukrainian art. The older generation suffered under the Soviet Union and now responds to any private enterprise with a joyful recognition of their own individuality. But the new generation of the Ukrainian left sees no fundamental difference among the elites, political or economic, who in their view are crowding out the average citizen. We can see other rhetorical battles of this kind playing out in parts over Facebook, periodically acted out by the artists Arseniy Zhilyaev, Yuri Albert, Kirill Medvedev, Yury Shabelnikov and others. After a while, one gets the sense that people of different social classes and intellectual levels keep attacking one another pointlessly with stereotypes about the other side. But that’s just my lyrical aside.

If we return to the works of architecture at the Assembly, it’s important to mention a new piece by Aleksei Buldakov and his Urban Fauna Laboratory. The work is in the form of a blueprint for a suburban neighborhood, zoned off on the basis of the behavior and movements of animals and birds. The model is rendered in wonderful watercolor, resulting in an overall look that is refreshing and wild.

Another popular category of works in the exhibit is the documentary video installation with elements of fiction, otherwise known as “research art.” In their introduction, the curators write that “in the worst case, the research becomes an image-maker for soft capitalism, in the same way that ‘autonomous’ art was and remains the face of so-called freedom and democracy.” The exhibit would have benefited from a new set of research installations, but it seems the curators had no way to get them. Many of the artists they selected stick to boring, previously trodden paths. For example, a film by the Chinese artist Wong Men Hoi, on display at the Institute of Pines and Prison Rations, profiles former members of the Norwegian communist party through endless interviews. The Institute of Zoology, meanwhile, contains a single a work: a video by Jan Peter Hammer about killer whales and the role of aqua parks in sensory deprivation experiments.

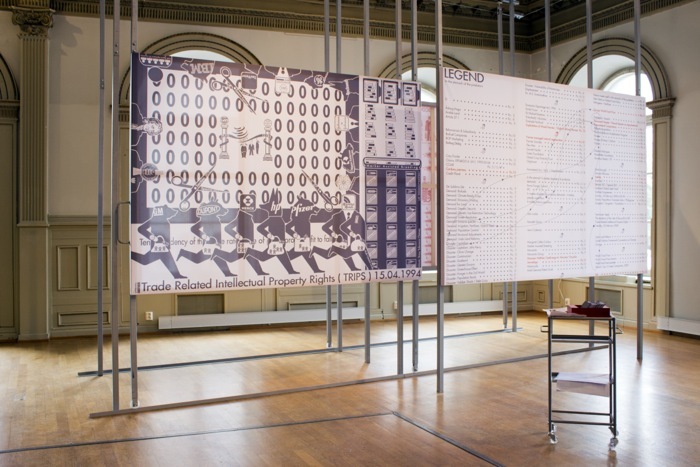

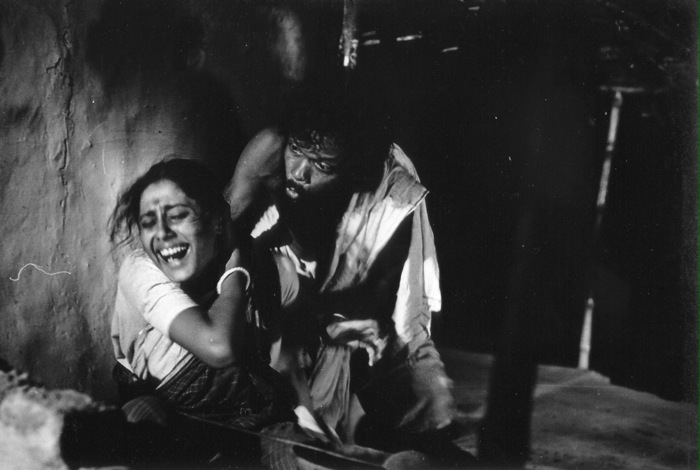

To their credit, the curators periodically break up the measured flow of revelatory installations with works of a different kind. “In the Stomach of the Predator” (2012-2013), a tangled piece by Andreas Siekmann and Alice Creischer, explores the sinister role of corporations in the growth and distribution of produce. The work is accompanied by an excerpt from the movie “In Search of Famine” (1980) by the Indian director Mrinal Sen, which follows a group of documentary filmmakers as they search for evidence of a terrible famine in 1943 that took the lives of more than five million Indians, but went largely unnoticed amid the turmoil of World War Two. The filmmakers in the film have a hard time obtaining evidence: their witnesses stumble; their photographs appear to match the event but seem to be from a different time period, and so on. Whether they meant to or not, the curators draw a question mark above the competency of the artist-as-researcher: he wants to tell the truth, but can he succeed?

The aforementioned Institute of Tropical Fascism is built around a monument to a fascist eagle that was found by the project curator in Peru. It’s a sensitive issue, no doubt about it, but isn’t it too politically correct to touch on Nazism in the tropics but leave out all mention of Nordic fascism? However, that wouldn’t be altogether true. The topic of fascism in Norway appears in the work of Olga Yegorova (Tsaplya) from the group Chto Delat?. The group is also the author of a piece that exemplifies another popular genre in leftist art: political theater. Their 2013 production, “A Border Musical,” tells the story of a young Russian woman named Tanya largely through songs reminiscent of the hymns of the Russian Salvation Army choir. Tanya marries a Norwegian man (a popular practice, apparently) and moves with her son to the new country. The locals believe Tanya is too harsh with her son and report her to social services, who take the child from the mother. “You see,” Olga explained, “Norway is a country where feminism has won. And that means all women have the same right to care for another person’s child. But to take a woman’s son from her—that’s fascism!” Actually, the practice is more reminiscent of the century-old socialist utopia, in which men, women and children essentially become common property. But I don’t mean to nag; the aim of political theater is to make society better, and Yegorova said “Musical” has already been shown to social workers in Norway to encourage them to deal less harshly with Russian immigrants.

Other examples of political theater at the Assembly are less focused on concrete issues and evoke contradictory feelings. The satirical “Machines of Love” (2012) by the philosopher Keti Choukhrov is at times so narrowly focused that it makes the viewer feel like a voyeurist.

In their article for the catalogue, Degot and Riff refer to themselves as “vehement anti-formalists.” The part of the exhibit devoted to the curators’ pet theme is, correspondingly, the Institute of Anti-Formalism. It predictably features works by Dmitry Gutov, who references the Marxian critic Mikhail Lifshits; the Polish avant-garde painter Wladyslaw Strzeminski, who accepted the post-war, pro-Soviet regime but was plagued by censorship; and the German zoologist and marginal artist Carl Friedrich Claus, among others. The leftist critique of formalism can be interpreted in various ways (personally, I find it unconvincing). But what’s more interesting is that with the Bergen Assembly, Degot and Riff finally succeeded in creating an exhibit that is free of the “aura” described by the pioneering modernist, Walter Benjamin. It features two painters, Kabakov and Gutov, but their paintings are actually simulative. Kabakov’s works are attributed to the made-up artist Charles Rozenthal, while Gutov, inturn, can “dig or not dig,” as they say in the army. Another aspect that is missing from the Assembly is the participatory art that is so popular among the leftist milieu; the aura that arises from the visitor’s touch has disappeared. Degot and Riff make do without it the same way that Voltaire made do without the idea of God. The reason is clear: aura means singularity, singularity means demand, and demand means capitalism. The curators were aiming for a similar effect with their piece “Shockworkers of the Mobile Image,” in which a historic building with traces of human presence that once housed the printing office of the Ural Worker newspaper is confronted with the imperious hand of nature, which attempts to impose artistic order against the curators’ will.

With the Assembly, the curators lucked out with the entire ensemble. Bergen itself is an unbelievably clean and coherent city (and everyone here knows English: once, I had an interesting conversation with a security guard at the building where Assembly parties took place about the comparative ease of taming a crowd at a hip-hop concert versus a heavy-metal concert). And the emphasis is on science fiction, where the ideal human existence is often portrayed as snow-white and soft to the touch, free from individual traumas and neuroses. Whatever you may think of the battle with aura, Degot and Riff have defeated it hands down. They succeeded in disarming our own inner sleeping (or hyperactive) Ivan Babich, the main character of Yuri Olesha’s dystopian novel “Envy,” by way of the sheer quality, scale, and internal logic of the exhibit.

Of course, the entire thing is a conceptual hallucination, but one that is masterfully rendered. On the way home I stopped at Oslo to see an exhibit of the local artist Ida Ekblad at the Museum of Contemporary Art. Ekblad is an expressionist who was raised on American images; at times she wears the costume of Willem de Kooning, at other times Robert Raschenberg, and even both at once. She writes texts reminiscent of the beatniks, she collects trash and arranges it in the manner of ikebana. She’s not original, to be sure, but she is talented. It was the same with African-American jazz, which was canonical and full of masterful recordings; but there were also foreign musicians who could spark delight in the audience by virtue of being so like their heroes. In other words, they were similar and different in the exact amount that enabled them to emulate human breathing in a saxophone solo. Degot and Riff owe their success to the conceptualism that raised them, both foreign and the kind in Moscow, where jazz vinyls were a rarity. It’s like Woody Allen’s character, a jazz connoisseur, says in the film “Anything Else:” “You know, there is also a little something else.”